Philadelphia's American League franchise entered its 50th season -- and its first of the post-Connie Mack era -- in the spring of 1951. New manager Jimmy Dykes led the A's to an 18-win improvement over the '50 squad. The team improved again in 1952, finishing in fourth place with a 79-75 record.

The Athletics would not finish above .500 or higher than sixth place in the AL until they got to Oakland 16 years later. Today we'll revisit the cross-country journey of this beleaguered franchise in Part II -- The Kansas City AAAs.

⚾

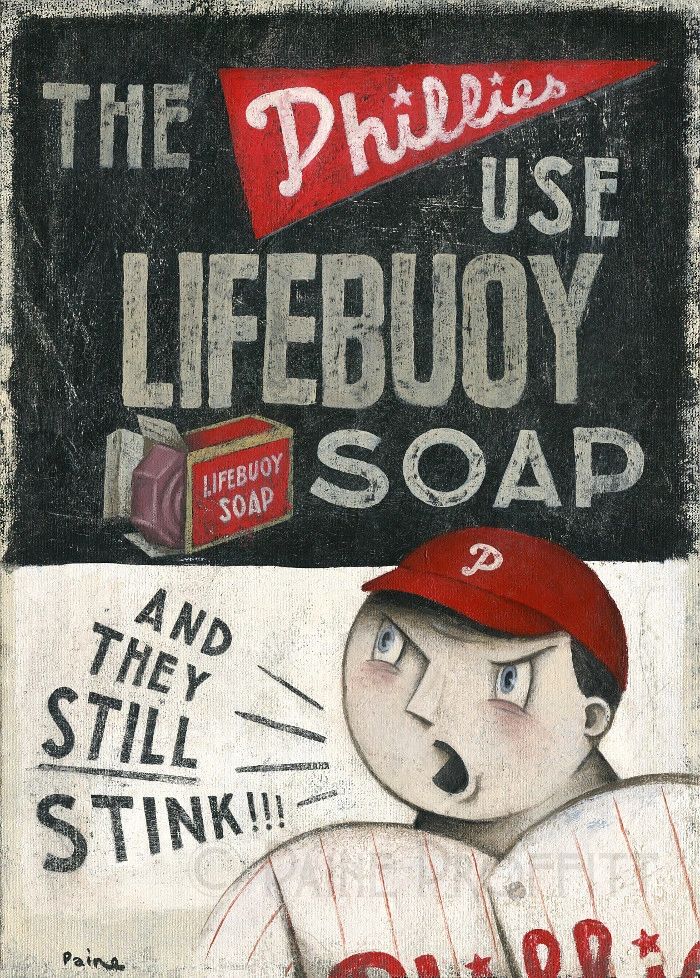

Throughout

the 1950s, several franchises moved out of cities with a more popular

team in town: the Browns conceded St. Louis to the Cardinals, the Braves

conceded Boston to the Red Sox. Philadelphia had one franchise with

five World Series victories and eight league crowns, and one franchise

with a single pennant and no championships. One team had ended a franchise-worst streak of 13 sub-.500 seasons with three straight winning campaigns, while the other sputtered through a 30-year stretch in which they posted a winning record once.

The Athletics and Phillies, playing home games at what would soon be called Connie Mack Stadium, finished the 1949 season with identical 81-73 records and near-identical attendance figures. The NL's Phillies had been the lesser franchise on the field yet crucially maintained strong support and turned the corner at the right time.

The Phillies rode a talented group of young stars all the way to the World Series in 1950. Four Phils finished in the top seven in NL MVP voting that year. Relief ace Jim Konstanty won the award after earning 16 wins and a league-high 22 saves (which wasn't an official stat until 1969.)

Shantz was also the smallest player ever to win MVP honors. At just 5 '6" and 140 lb, he was about 25 pounds lighter than current Astros superstar Jose Altuve. Johnny Evers earned NL MVP honors in 1914 despite weighing a ghastly 125 lb - though he was three inches taller than Shantz.

1952 proved to be a "dead cat bounce" season for Shantz and the Athletics, as both the team and its diminutive ace regressed in 1953. All-Star Gus Zernial smacked a career-high 42 home runs, finishing one behind AL MVP Al Rosen for the league lead. However Zernial had little protection in the lineup and the pitching staff was mediocre, despite boasting the previous year's MVP and Rookie of the Year.

| source |

Connie Mack was in his nineties and the franchise was severely in debt. Attendance at the stadium that bore Mack's name was sparse.

While many locals called for the Mack family to sell the team, the city organized a “Save the A’s” campaign in the summer of 1954 when it became obvious the Athletics were at risk of being sold and moved, putting the onus on the fans to support the club and keep it in Philly.

Sound familiar? The Athletics were soon sold to Arnold Johnson, who promptly relocated the club to Kansas City.

Pitching was still a problem, as the A's ranked dead last in team ERA for the second year in a row. Young hurlers Art Ditmar, Arnie Portocarrero, and Art Ceccarelli (triple "A"s) were clearly overmatched. [On a less relevant but more personal note, Ceccarelli is one of a handful of pro athletes from my hometown and the only major league baseball player who attended my high school.]

In return, Kansas City received pitcher Don Larsen, who had a down year in '59 but was still an effective starter, Norm Siebern, a left handed hitting corner outfielder who batted .271 with 11 home runs for the Yanks and - like Maris - was entering his prime, Marv Throneberry, who was a marginal upgrade over Hadley at first base, and Hank Bauer... who was 37 and no longer an everyday starter.

Counterpoint: it was the Yankees. Again. During Arnold Johnson's six seasons as A's owner the team swapped players with the Yanks an astounding 14 times. Kansas City did come out on top in a couple deals but on balance these trades decimated the Athletics and prolonged the Yankee dynasty.

Two expansion franchises joined the AL in 1961, and the 154-game schedule swelled to the 162-game season still in place today. K.C. finished tied with the new Washington Senators for last in the A.L. with 100 losses - nine games behind the other expansion squad, the Los Angeles Angels of Los Angeles.

Siebern and 29 year-old rookie pitcher Jim Archer were the only players on the 1961 A's above replacement level. Both expansion squads had at least one pitcher who would have been the A's ace. Both expansion squads had five players with double-digit home runs; the Angels had three players with a higher OPS than Kansas City's best player.

Kansas City and Baltimore swapped first basemen after the 1963 season, with Siebern rejoining Bauer for the '64 and '65 campaigns. The financially struggling A's received $25,000 cash and Jim Gentile, who was named to every AL All-Star team from 1960-62. Unlike Siebern, Gentile wouldn't be the lone bright spot in a lackluster lineup. Finley also acquired slugging outfielder Rocky Colavito from the Tigers.

| source |

The first pick in the first-ever MLB draft belonged to the Kansas City Athletics, who selected Arizona State outfielder Rick Monday.

During the 1965 season, Kansas City's woeful pitching staff got a boost from two future Hall of Famers. The first was Hunter, who pitched 133 innings as a 19 year-old rookie. The second HOFer started K.C.'s second-to-last home game, pitching three scoreless innings against the Red Sox.

|

| source |

"Satchel Paige Day" was a gimmick, but a successful one. The day prior, Hunter had shut out the Red Sox in front of 2,304 fans. Two days earlier, the A's beat Washington 8-7 before an intimate gathering of just 690 spectators (John Fisher hasn't sunk his A's that low -- yet.) The team's final home game was attended by 2,874 patrons. Satchel's start attracted 9,289 paying customers - one of the largest crowds of the 1965 season.

In 1966 the Athletics fully embraced a youth movement, as manager Al Dark handed the ball to a starter under the age of 25 in over 70% of the team's games. The best of the bunch appeared to be Jim Nash, who finished second in Rookie of the Year voting after a 12-1 season in which he posted a tidy 2.06 ERA.

The light-hitting lineup was young, too, with only one starter (third baseman Ed Charles) older than 26. Utility man Roger Repoz was the only Athletic to reach double figures in home runs, with 11 in 319 at-bats. The A's wouldn't stay powerless for long, however.

~

Once again, beautifully researched and presented, Chris! The Yanks certainly benefitted from the AAAs in the 60s.

ReplyDeleteThe red and blue uniforms always throw me, I always think its a different team. Weird to think of them wearing anything but green.

ReplyDeleteCrazy to think there were only 690 people at that one game. Thanks for doing this series. Although some of the names were familiar... I've got to admit I don't know a lot about the A's before their arrival in Oakland. I'm trying to figure out what direction my collection will be headed when the A's move to Vegas. One of the options is to focus on the Kansas and Philadelphia stuff instead of the Vegas era stuff.

ReplyDeleteThere still may be many retired stars of the Oakland teams that come up in future releases that may keep you busy if you like that stuff

Delete👍

ReplyDeletePeople always mention how thin Johnny Evers was, like it was a bad thing, but it was obviously just the way he was built. He wasn't unhealthy, and clearly his weight, or lack thereof, never affected his playing ability in the least.

ReplyDeleteNobody could've ever predicted Roger Maris' couple of years of greatness. It was just one of those seemingly freak stretches that's happened to so many other guys over the course of baseball's history.

I'm a little behind in my reading, but it's posts like this one that keep me from just skipping the lot.

ReplyDelete